Why Most Americans Who Need Substance Use Disorder Treatment Don’t Get It

Counseling Schools Search

When you click on a sponsoring school or program advertised on our site, or fill out a form to request information from a sponsoring school, we may earn a commission. View our advertising disclosure for more details.

More than 38 million adults with a substance use disorder did not receive treatment in 2024, according to the latest data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. That is more than 80 percent of the 48.4 million individuals defined as needing treatment.

More than 95 percent of those not receiving treatment didn’t believe they needed help—but for 1.5 million adults who thought they did, barriers to treatment left them unwilling or unable to get support.

CounselingSchools analyzed findings from the 2024 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (the most recent data available as of January 2026), compiled by SAMHSA, to highlight the most common barriers to care for adults seeking substance abuse treatment. Among these obstacles are stigma, a lack of access, various socioeconomic factors and inequities, and a person believing they could handle their disorder on their own.

What Causes a Substance Use Disorder?

A substance use disorder (SUD) is caused by shifts in brain structure and function due to a pattern of substance use (including alcohol) that renders further use compulsive. These chronic conditions range in severity from mild to severe while impacting cognitive, behavioral, and physiological systems and making treatment notoriously difficult. SUDs have enormous potential to cause long-term negative impacts on people’s health, relationships, home lives, careers, and education. Changes in brain chemistry may cause some with SUDs to act out of character by lying, stealing, or showing aggression—actions that can further alienate individuals from loved ones while reinforcing stigmas around substance abuse.

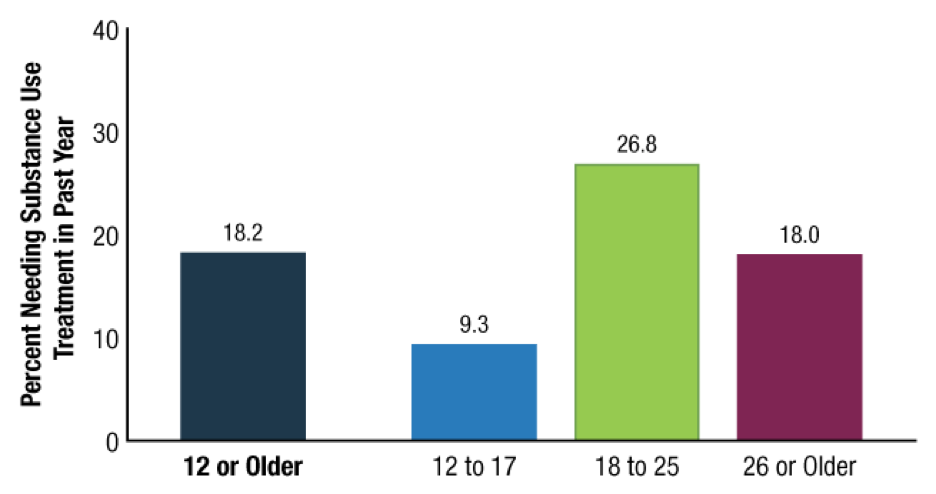

In 2024, the 18- to 25-year-old age group represented the largest percentage of adults who reported having a SUD in the last year, with more than a quarter of people participating in the SAMHSA survey making that claim.

Figure 69. Need for Substance Use Treatment in the Past Year: Among People Aged 12 or Older; 2024

Note: The “Need for Substance Use Treatment” is defined as having a substance use disorder in the past year or receiving substance use treatment in the past year.

Treating substance use is among the most expensive health issues in the United States. The Biden administration in 2024 budgeted $10.8 billion for SAMHSA—up $3.3 billion the year prior—with $5.7 billion earmarked for substance use prevention and treatment. In 2023, the total budget for SAMHSA reached $9.7 billion. Cumulative spending for mental health and SUD treatment from public and private sources was an estimated $280.5 billion in 2020, the latest data available as of January 2026.

The National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics reports that in 2024, “The cost of drug abuse in the US is nearly $820 billion per year, taking into account crime, healthcare needs, lost work productivity, and other impacts on society.”

The constellation of care options for SUDs can be complicated to navigate, as successful treatment options are often multi-pronged and specific to an individual. Care may include inpatient and outpatient services, medications, individual and group counseling, case management with a social worker, and more.

Research into substance use science and treatment has afforded the medical community a better appreciation for addressing the full breadth of a patient’s needs, such as putting a focus on mental healthcare and tailoring specific treatment plans and therapy.

A multidisciplinary approach to care is paramount to tackling the complex symptoms of SUDs, while coordination between caregivers ensures any prescribed medications are complementary (especially if comorbidities such as anxiety or depression are present in a patient) and that the care provided by clinical social workers, psychiatrists, and other professionals works together holistically.

Keep reading to learn more about barriers to care for individuals living with SUDs.

Why Americans Don’t Get Help

Americans have several reasons for not seeking help with substance use disorders. According to SAMHSA, these barriers included:

- Thought it would cost too much

- Did not have health insurance coverage for drug or alcohol use treatment

- Health insurance would not pay enough of the cost of treatment

- Did not know how or where to get treatment

- Could not find a treatment program or healthcare professionals they wanted to go to

- Lack of openings in the treatment program or the healthcare professional they wanted to go to

- Problems with things like transportation, childcare, or getting appointments at times that worked for them

- Not enough time for treatment

- Worries that information would not be kept private

75.5 Percent of Adults With Untreated SUDs Thought They Should Handle It on Their Own

An analysis of the SAMHSA survey shows that more than three-quarters of adults who did not get treatment for SUDs in 2024 thought they should be able to manage their disease without seeking help. Not being ready to start treatment accounted for 65.0 percent of the top reasons, and 59.5 percent weren’t prepared to stop or decrease their use. The SAMHSA survey allowed for multiple answers.

People living with SUDs may be unwilling to seek treatment at a detox center or rehab program if they think their SUD isn’t “bad enough” to warrant it or if they think they can manage their disorder themselves.

The cost of care dissuaded about 45.3 percent of respondents. The average cost of drug rehabilitation is $13,475 per person, according to the National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics.

Stigma Remains a Major Barrier to Treatment

Discrimination against and stigmatization of people living with SUDs are still commonplace despite the relaxation of punitive drug policies in the U.S. Notably, 43.2 percent of those surveyed by SAMHSA said they did not pursue treatment out of worry over what others might think or say.

People’s attitudes around the cause and controllability of SUDs play into stigmatization, according to an empirical investigation published in 2010 in the Journal of Drug Issues.

How people label the behaviors of those with SUDS—or characterize the individuals themselves—can impact others’ understanding and have a domino effect on a larger scale. Public perception affects how policymakers allocate resources, the willingness of some providers to screen and address SUDs, and the desire for people living with SUDs to seek or accept treatment themselves.

Fear and shame around breaches of confidentiality are also of major concern for people with SUDs who didn’t get treatment: 34.4 percent thought that if people knew they were receiving care, negative repercussions would occur up to and including the loss of their job, home, or children. Thirty-three percent were deterred by the idea that people would find out their private information about their SUD treatment.

Stigmas also play heavily into racial inequities when it comes to treatment. Drug policies in the U.S.—such as the War on Drugs in the 70s and the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986—have historically criminalized Black Americans with substance use, deterring them from getting needed treatment.

Racial bias in the healthcare system further contributes to treatment gaps. In a study released in 2023 by researchers at Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, white patients with opioid use disorders (OUD) who experienced an infection, overdose, or other high-risk event received and filled prescriptions as much as 80 percent more frequently than Black patients and 25 percent more than Hispanic patients, among Medicare beneficiaries with active OUD symptoms and disability.

The study’s authors concluded: “These disparities are unlikely to close without the structural barriers and structural racism obstructing equitable access to medications for OUD, such as stigma and geographic maldistribution of relevant providers, being addressed.”

Access To Care Is Crucial

Those who do want to seek treatment may face a range of barriers inhibiting access to services, including a lack of capacity to meet demand, or, for adults living with SUD, insufficient health insurance to cover it. Nearly 32.4 percent of respondents said their health insurance wouldn’t cover enough of the costs to make it feasible.

Treatment can also be logistically impractical and time-intensive. People needing time off work might experience anxiety over losing their jobs and affording healthcare, childcare, or housing. Care may also be geographically far—even hours—away, particularly for people living rurally with large service areas. Long distances require even more logistics around transportation, time, and accommodations.

Barriers to receiving care in the U.S. can be high—but so can the toll on those not receiving vital treatment. Emergency department visits for alcohol use disorders and SUDs rose by 30 percent on average between 2014 and 2018 in the U.S., while SUD-related hospitalizations climbed by 57 percent, according to a study published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

At the same time, experts are understanding more about gender- and race-based inequities when it comes to treatment due to a growing body of research that leverages an intersectional approach to the study of SUD treatment. Additional research like this, along with the dismantling of stigmas and increased access to essential care, can begin to remove some of the most common barriers to SUD treatment.

Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) is part of substance use disorder. The barriers discussed above apply to OUD, but according to a 2024 report from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), there are additional barriers to treatment. Like most disorders, clinicians can treat OUD with therapy and/or medications. However, some clinicians equate treating OUD with medications with illegal substance use. Some facilities offering OUD treatment won’t accept clients using medications.

Methadone for OUD is highly restricted, so although effective, prescribing it is limited. Buprenorphine, an effective treatment for OUD, does not have the restrictions that methadone does. Unfortunately, according to the CDC, many pharmacies don’t carry buprenorphine. Additionally, until 2023, prescribers were required to undergo training and obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine. Others chose to not prescribe it for fear of “being inundated with requests for buprenorphine.”